Represented by Portas Vilaseca Galeria in Brazil, artist Carolina Martinez opens this Saturday (February, 26) at Galerie Ilian Rebei, in Paris, her first solo show in Europe.

Featuring a text by Brazilian art critic, curator and researcher Fernanda Lopes, “Alvorada” ( L’Aube / The Dawn ) brings together a set of 10 new works that renew and reaffirm the Rio de Janeiro-based artist’s interest in empty spaces and unusual angles, but that also reveal the construction of a new pictorial personality.

.

The show runs until March 28. More information: www.ilianrebei.com

***

CRITICAL TEXT

by Fernanda Lopes*

The exhibition Alvorada that Carolina Martinez presents at Galerie Ilian Rebei is like a landmark, at the same time, of apex and rupture within her production. A continuation and also a fresh start. In this dawn by the Brazilian artist – her first solo show on the European continent – we are led to experience, in the set of ten paintings of different formats from her recent production, seen for the first time now, a place between the real and the invented, investigated by her in little more 10 years of production.

Carolina has been building a body of work that moves like provocations – from the pictorial plane, the image, the space and, perhaps above all, the gaze. Architectural spaces and urban surfaces have always occupied a fundamental place in this process. The spaces built by the artist are the result of a research of images of architecture, especially modern, in Brazil and abroad. Some of these images are made by third parties and others are made by the artist herself. The physical and historical grandeur of this type of construction contrasts with the unusual angles that Carolina’s paintings, photographs and collages reveal, usually emphasizing emptiness and a kind of melancholy or frustration. It is curious because, despite being works where the human body never appears visually, the angles and cuts they present, only a body present in space could perceive and reveal.

It is as if a certain rationality and purity of the modern project were left aside to point to the experience of the body that inhabits this space, and even to understand this space as a kind of body, with its own personality and characteristics. Angles, scales, framing, the application of sheets of wood and the modular logic of some works are conductors of the artist’s provocations, to the pictorial plane, to the surface of the painting, and also to the viewer’s own gaze. How is it possible to rediscover places that seem at the same time so close and so indifferent? Space that seems to oscillate between memories and forgetfulness.

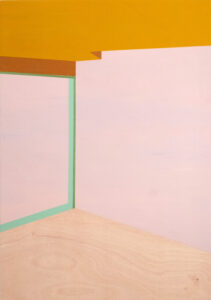

The recent works gathered in Alvorada renew and reaffirm the artist’s interest in architecture, but there is also something new in these paintings: Carolina Martinez’s relationship with color. Previous works are marked by neutral tones, which were largely responsible for the silent, empty and melancholy atmosphere of the spaces we saw until then. The color was applied to the surface practically in its raw form, without mixing, varying only between lighter and darker tones. The use of spray and not brush also reaffirmed a certain impersonality of color.

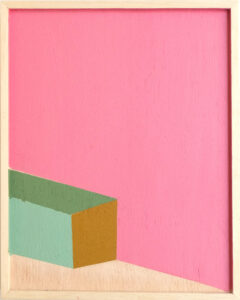

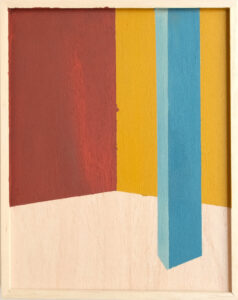

What we see now is a rediscovery of color and the possibilities it brings to work. The need for isolation and the restrictions of the last two years caused by the COVID pandemic meant that Carolina had to deal with some tubes of colored paint that she kept in her studio, but that she found it difficult to use. She began mixing and producing her own colors from them, in a process of trial and error, generating her own pinks, blues, greens, ochers and yellows. Likewise, in the plural, because if we look carefully, these colors are repeated in the works in the exhibition, but in slightly different shades. And they inhabit and build in an almost unexpected way the spaces we see – which remain without human figures, but do not necessarily evoke the feeling of emptiness that we had until then. The artificiality and autonomy of these other colors underscore the idea that what we see is not the reproduction of a place or a situation, but effectively the construction of it and the painting as well. Another atmosphere, now flirting with abstraction, is constituted from the “personality” that each of these new colors carries, and that are evidenced and multiplied as they are built with the irregularity of the brushstrokes, evidencing the veins and drawings of the surface of wood, and placed in relation – between them and between the spaces inside and outside the painting.

In the smaller paintings, closer framings are presented, which transform the spatial details almost into abstractions. Inventions where geometric rationality is put in check, orbiting around planes of color. In the larger paintings, some articulated in modules while others are structured on a single wooden board, these colour planes are articulated in an even more complex way. And even when the works carry narrative titles, such as In the colour where I find you, Cliff or Memories of what I have not seen, they still insist on flirting with a certain abstraction. It is necessary to find there, among angles, scales, framing and, especially, colors, a place for these titles-provocation.

Here it is important to draw attention to a genealogy of Brazilian art, in one of its many possibilities structured from the relationship with color. In this story, the poetic trajectory of Hélio Oiticica between the 1950s and 1970s is a fundamental landmark. From his Metaesquemas, through Bólides, Parangolés and Penetráveis, there is an interest in color that takes shape and the body of the spectator, and launches itself into space, inside and outside the museum, inside and outside the limits of art. It is color, which is no longer thought of as a complement or filling of form, putting aside a relationship with the world and with reality based on principles of representation, to start being thought of as a structuring element of the entire work. The color, which flirts and tensions the tropical cliché that the south had and still has to deal with. It is the autonomy of thought from the autonomy of color. These are apparently very simple gestures, but they are where everything happens.

* Fenanda Lopes is an art critic, curator and researcher. She holds a doctoral degree from the School of Fine Arts of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and is the author of A experiência Rex: “éramos o Time do Rei” (2009) and Área experimental: lugar, espaço e dimensão do experimental na arte brasileira dos anos 1970 (2013). She worked as adjunct curator at the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro (2016-2020) where in 2017, alongside Fernando Cocchiarale, received the Maria Eugênia Franco Award, granted by the Brazilian Association of Art Critics for curating the exhibition In a frenzy – A panorama of MAM Rio collections (2016).

***

PICTURES GALLERY

- Alvorada, 25 x 20 cm, Acrílica sobre mandeira [ Acrylic on wood ]

- Cliff, 130 x 90 cm, Acrílica sobre madeira [ Acrylic on wood ]

- Everyday life in colour I, 25 x 20 cm, Acrílica sobre madeira [ Acrylic on wood ]

- Everyday life in colour II, 25 x 20 cm, Acrílica sobre madeira [ Acrylic on wood ]

- Everyday life in colour III, 25 x 20 cm, Acrílica sobre madeira [ Acrylic on wood ]

- Maze, 130 x 90 cm, Acrílica sobre madeira [ Acrylic on wood ]

- In the colour where I find you, 160 x 240 cm, Acrílica sobre madeira [ Acrylic on wood ]

- Memories of what I have not seen, 120 x 150 cm, Acrílica sobre madeira [ Acrylic on wood ]

- Untitled I, 40 x 50 cm, Acrílica sobre madeira [ Acrylic on wood ]

- Untitled II, 40 x 50 cm, Acrílica sobre madeira [ Acrylic on wood ]